While the term “B-Movie” is often thrown around these days in conjunction with bad films, its initial use in Hollywood wasn’t a reflection of the quality (or lack thereof) of the film. As anyone alive during Hollywood’s golden era might tell you, theaters often showed a whole program of entertainment for one price. Audiences would see newsreels, cartoon shorts and two features- a B movie and an A movie. At first, theater owners used to put these presentations together themselves; they might choose some Universal newsreels, Disney cartoons, a Columbia B film and an MGM A film.

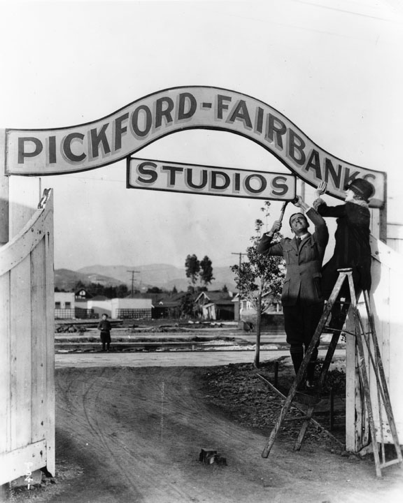

At first, Hollywood got its B-Films from “Poverty Row”, a cluster of low budget film studios mostly located on Gower Street in Hollywood. Poverty Row studios provided an outlet for the aspiring actors and actresses who streamed into town but couldn’t get a contract at one of the majors. (It was several steps up from making “stag” films.) Poverty Row’s films at this time were pretty much what you might expect from a B-Film. Made on makeshift soundstages with equipment rented from the majors, these films were hardly competition for the newest MGM musical or Paramount comedy.

While the majors were originally willing to leave B-Films to Poverty Row, they soon began to see the benefits of dipping a toe into the lower end business. The majors, with their guaranteed contracts and massive overhead, often had much of their studio lots going idle waiting for the next big picture. Louis B. Mayer realized that he could put these resources to use making B-Films. Of course, none of his biggest stars would be used for these films. Instead, an actor who found himself as a supporting actor in the biggest MGM Pictures could become a leading man in a B-Film. Mr. Mayer and his fellow executives in the major studios could thus utilize wasted resources and setup a sort of minor league for motion pictures. Prove that you can tackle a leading role and you might make it as a leading actor in the A-Films.

While the B-Films made by the majors were much cheaper than their A-Film content, they were still more expensive than those made by Poverty Row. This caused a small problem for the majors. With a major picture at the top of the marquee, a theater owner could put anything else under it and get a crowd. Why pay extra for a B-Film from MGM? Block booking and purchasing their own theater chains fixed that problem. MGM had Loews Theaters; Paramount and Fox had their own chains. These chains would only book the films of their respective studios. Furthermore, independent exhibitors were told that if they wanted to show a studio’s A-Film they would have to book the studio’s B-Film, newsreels, cartoons, etc.

The major studios began bulking up their offerings so that they could fill out a program. RKO chose to distribute Disney’s cartoons alongside their films. MGM and Warner Brothers setup their own animation studios. Jack Warner had open contempt for animation- he famously thought that his studio owned Mickey Mouse- but he wanted to control his studio’s full slate so Warner Brothers bulked up its operations.

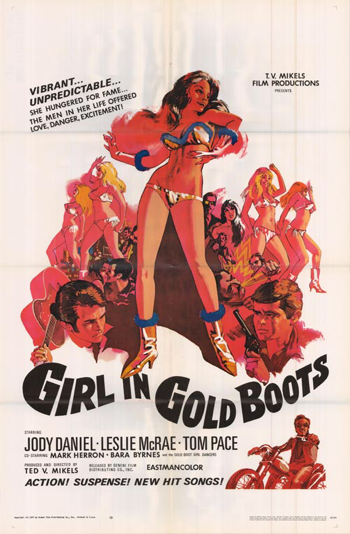

The minors, however, wouldn’t hand over their business without a fight. An anti-trust action was filed against the major studios that resulted in a court order ending block booking and forcing the divestiture of the studio’s theater chains. With block booking ended, Poverty Row saw blue skies again, though that wouldn’t last long. The media world shifted, ending the days of multi-film programming. Poverty Row had to either give up or grow up. Most of them gave up. The films that normally would have been considered B’s ended up finding a home at drive-ins and became mostly genre films. The majors wouldn’t get out of things unscathed. Columbia and Disney would move up to become major studios. The mighty MGM would fall down to become a minor studio and RKO would just disappear.